Policy»

Info

This feature is only available to paid Spacelift accounts. Please check out our pricing page for more information.

Policy-as-code is the idea of expressing rules using a high-level programming language and treating them as you normally treat code, which includes version control as well as continuous integration and deployment. This approach extends the infrastructure-as-code approach to also cover the rules governing this infrastructure, and the platform that manages it.

Spacelift as a development platform is built around this concept and allows defining policies that involve various decision points in the application. User-defined policies can decide:

- Login: Who gets to log in to your Spacelift account and with what level of access.

- Access: Who gets to access individual Stacks and with what level of access. Access policies have been replaced by space access control.

- Approval: Who can approve or reject a run and how a run can be approved.

- Initialization: Which runs and tasks can be started. Initialization policies have been replaced by approval policies.

- Notification: Routing and filtering notifications.

- Plan: Which changes can be applied.

- Push: How Git push events are interpreted.

- Task: Which one-off commands can be executed. Task run policies have been replaced by approval policies.

- Trigger: What happens when blocking runs terminate. Trigger policies have been mostly replaced by stack dependencies.

Please refer to the following table for information on what each policy types returns, and the rules available within each policy.

| Type | Purpose | Types | Returns | Rules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Login | Allow or deny login, grant admin access | Positive and negative | boolean |

allow, admin, deny, deny_admin |

| Access | Grant or deny appropriate level of stack access | Positive and negative | boolean |

read, write, deny, deny_write |

| Approval | Who can approve or reject a run and how a run can be approved | Positive and negative | boolean |

approve, reject |

| Initialization | Blocks suspicious runs before they start | Negative | set<string> |

deny |

| Notification | Routes and filters notifications | Positive | map<string, any> |

inbox, slack, webhook |

| Plan | Gives feedback on runs after planning phase | Negative | set<string> |

deny, warn |

| Push | Determines how a Git push event is interpreted | Positive and negative | boolean |

track, propose, ignore, ignore_track, notrigger, notify |

| Task | Blocks suspicious tasks from running | Negative | set<string> |

deny |

| Trigger | Selects stacks for which to trigger a tracked run | Positive | set<string> |

trigger |

Tip

We maintain a library of example policies that are ready to use or alter to meet your specific needs.

For up-to-date policy input information you can also refer to official Spacelift policy contract schema.

If you cannot find what you are looking for, please reach out to our support and we will craft a policy to do exactly what you need.

How it works»

Spacelift uses an open-source project called Open Policy Agent and its rule language, Rego, to execute policies at various decision points.

You can think of policies as snippets of code that receive some JSON-formatted input (the data needed to make a decision) and are allowed to produce an output in a predefined form. Each policy type exposes slightly different data, so please refer to their respective schemas for more information.

Login policies are global. All other policy types operate on the stack level and can be attached to multiple stacks, like contexts, which facilitates code reuse and allows flexibility. Policies only affect stacks they're attached to.

Multiple policies of the same type can be attached to a single stack, in which case they are evaluated separately to avoid having their code (like local variables and helper rules) affect one another. Once these policies are evaluated against the same input, their results are combined. So if you allow user login from one policy but deny it from another, the result will still be a denial.

OPA version»

We update the version of OPA that we are using regularly. To find out the version we are currently running, use this query:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

For more detailed information about the GraphQL API and its integration, please refer to the API documentation.

Policy language»

Rego, the language we're using to execute policies, is a very elegant, Turing incomplete data query language. If you know SQL and jq, you should find Rego familiar and only need a few hours to understand its quirks. For each policy, we also provide examples you can tweak to achieve your goals.

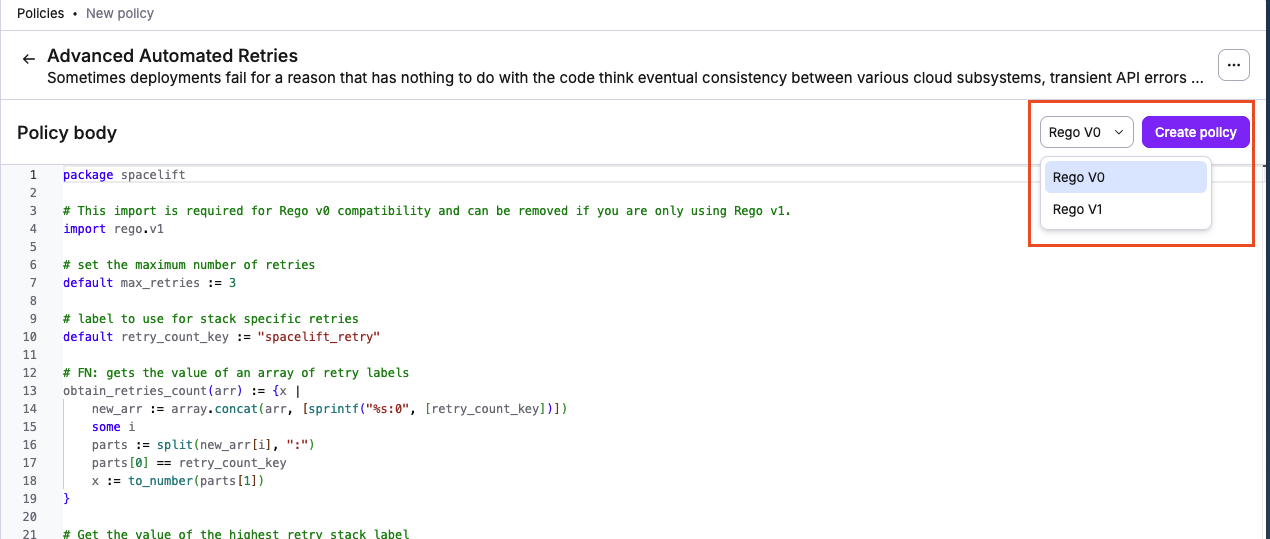

Rego version support»

Spacelift supports both Rego v0 and v1. You can switch between versions at any time when editing a policy using the version selector in the policy editor.

We recommend using Rego v1 for all new policies. Rego v1 introduces improved syntax and stricter semantics that make policies more robust and easier to maintain. For information on migrating existing policies from v0 to v1, see the OPA migration guide.

Rego constraints»

To keep policies functionally pure and relatively snappy, we disabled some Rego built-ins that can query external or runtime data. These are:

http.sendopa.runtimerego.parse_moduletime.now_nstrace

Policies must be self-contained and cannot refer to external resources (e.g. files in a VCS repository).

Info

Disabling time.now_ns may seem surprising, but depending on the current timestamp it can make your policies impure and thus tricky to test. We encourage you to test your policies thoroughly!

The current timestamp in Rego-compatible form (Unix nanoseconds) is available as spacelift.request.timestamp_ns in plan policy payloads, so please use it instead.

Policy returns and rules»

Please refer to the following table for information on what each policy types returns, and the rules available within each policy.

| Type | Purpose | Types | Returns | Rules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Login | Allow or deny login, grant admin access | Positive and negative | boolean |

allow, admin, deny, deny_admin |

| Access | Grant or deny appropriate level of stack access | Positive and negative | boolean |

read, write, deny, deny_write |

| Approval | Who can approve or reject a run and how a run can be approved | Positive and negative | boolean |

approve, reject |

| Initialization | Blocks suspicious runs before they start | Negative | set<string> |

deny |

| Notification | Routes and filters notifications | Positive | map<string, any> |

inbox, slack, webhook |

| Plan | Gives feedback on runs after planning phase | Negative | set<string> |

deny, warn |

| Push | Determines how a Git push event is interpreted | Positive and negative | boolean |

track, propose, ignore, ignore_track, notrigger, notify |

| Task | Blocks suspicious tasks from running | Negative | set<string> |

deny |

| Trigger | Selects stacks for which to trigger a tracked run | Positive | set<string> |

trigger |

Tip

We maintain a library of example policies that you can tweak to meet your specific needs or use as-is.

If you cannot find what you are looking for, please reach out to our support and we will craft a policy to do exactly what you need.

Boolean»

Login and access policies expect rules to return a boolean value (true or false). Each type of policy defines its own set of rules corresponding to different access levels. In these cases, various types of rules can be positive or negative (that is, they can explicitly allow or deny access).

Set of strings»

The second group of policies (initialization, plan, and task) is expected to generate a set of strings that serve as direct feedback to the user. Those rules are generally negative in that they can only block certain actions. Only their lack counts as an implicit success.

Here's a practical difference between the two types:

| boolean.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

| boolean.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

| string.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

| string.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

For the policies that generate a set of strings, you want these strings to be both informative and relevant, so you'll see this pattern a lot in the examples:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

Complex objects»

Notification policies will generate and return more complex objects, typically JSON objects. In terms of syntax, the returned values are still very similar to policies that return sets of strings, but they provide additional information inside the returned decision.

For example, this rule which will return a JSON object to be used when creating a custom notification:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

Helper functions»

The following helper functions can be used in Spacelift policies:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

output := sanitized(x) |

output is the string x sanitized using the same algorithm we use to sanitize secrets. |

result := exec(x) |

Executes the command x. result is an object containing status, stdout and stderr. Only applicable for run initialization policies for private workers. |

Creating policies»

You can create policies through the web UI and the Terraform provider. We generally suggest the latter, as it's much easier to manage down the line and allows proper unit testing.

With the Terraform provider»

Here's how you would define a plan policy in Terraform and attach it to a stack (also created here with minimal configuration):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

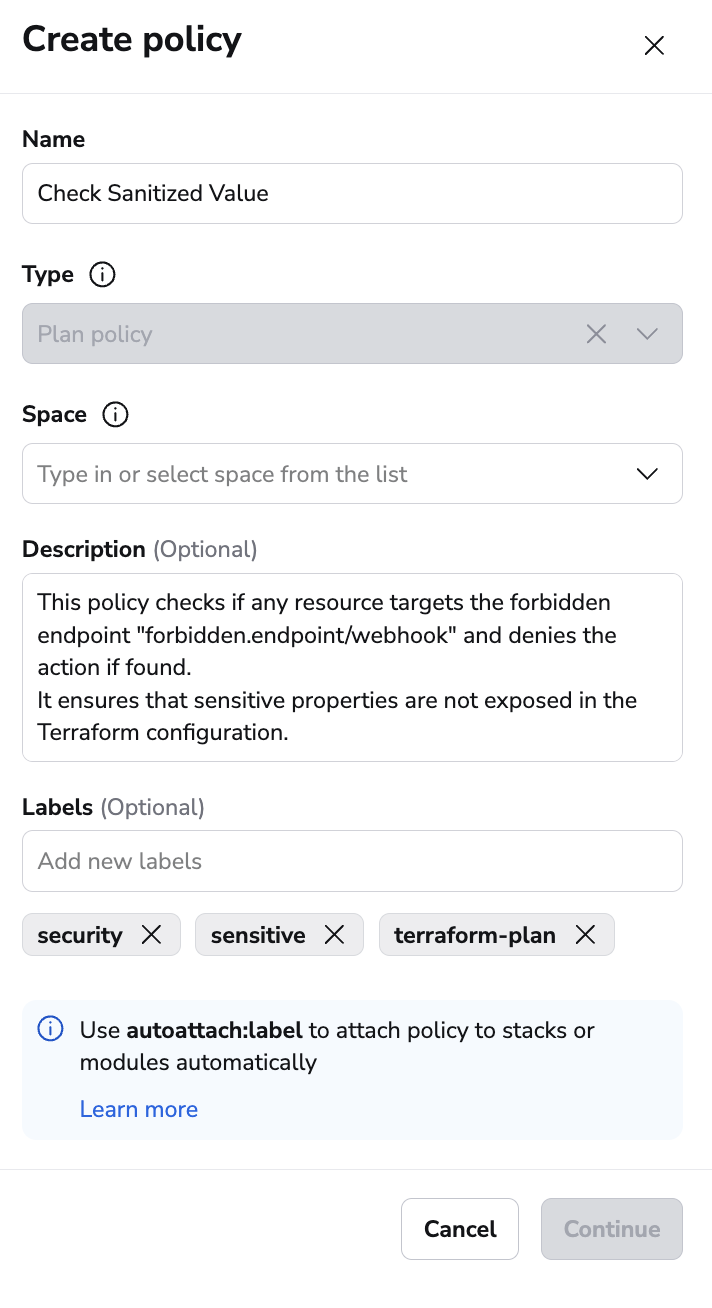

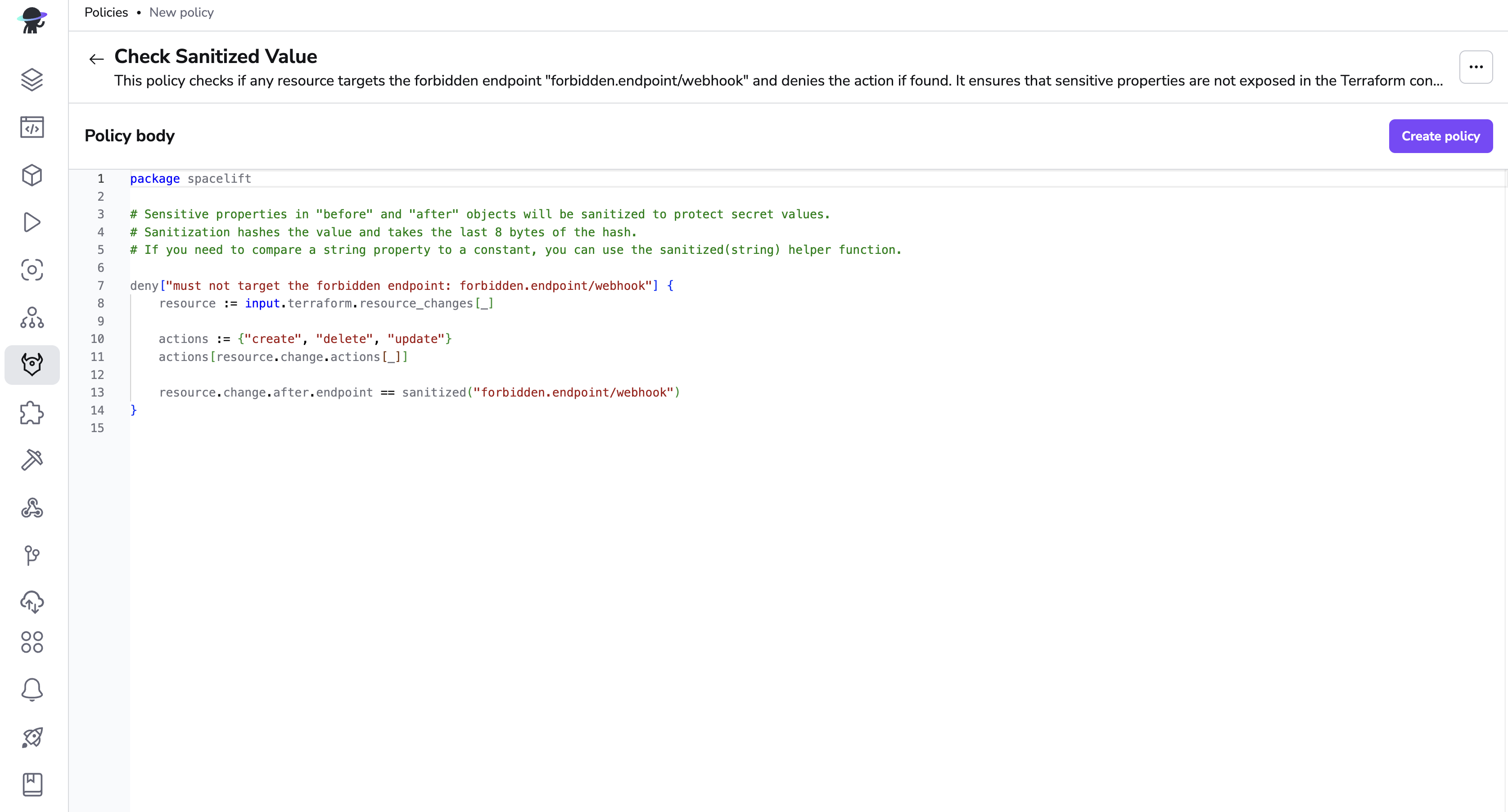

With the web UI»

You must be a Spacelift admin to manage policies.

You can create approval, push, plan, trigger, and notification policies in the web UI. Login policies are created in a different section of the UI.

- Navigate to the Enforce Guardrails > Policies tab in Spacelift.

- Click Create policy.

- Fill in the required policy details:

- Name: Enter a unique, descriptive name for the policy.

- Type: Select the type of policy from the dropdown.

- Space: Select the space to create the policy in.

- Description (optional): Enter a (markdown-supported) description for the policy.

- Labels (optional): Add labels to help sort and filter your policies. You can use

autoattach:labelto attach the policy to stacks or modules with the chosenlabelautomatically.

- Click Continue to edit the policy.

- You'll see an example policy body based on the type you chose. Remove the comments from any rules you'd like to apply and add or change rules as needed.

- Click Create policy. You can always edit policies as needed.

Policy structure»

We prepend variable definitions to each policy. These variables can be different for each type, but the prepended code is very similar. Here's an example for the Approval policy:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | |

Warning

You can't change predefined variable types. Doing so will result in a policy validation error and the policy won't be saved.

Attaching policies»

Automatically (with labels)»

With the exception of login policies, policies can be automatically attached to stacks using the autoattach:label special label. Replace label with the name of a label attached to stacks and/or modules in your Spacelift account you wish the policy to be attached to.

Policy attachment example»

Adding autoattach:needs_approval label to your policy will automatically attach the policy to all stacks/modules with the label needs_approval. This can be done with any label you're using on your stacks and modules.

Wildcard policy attachments»

You can also attach a policy to stacks/modules using a wildcard. For example, using autoattach:* as a label will attach the policy to all stacks/modules.

Manually»

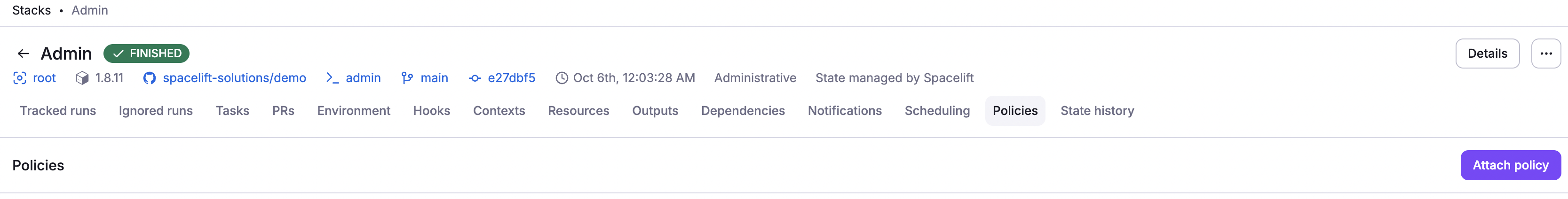

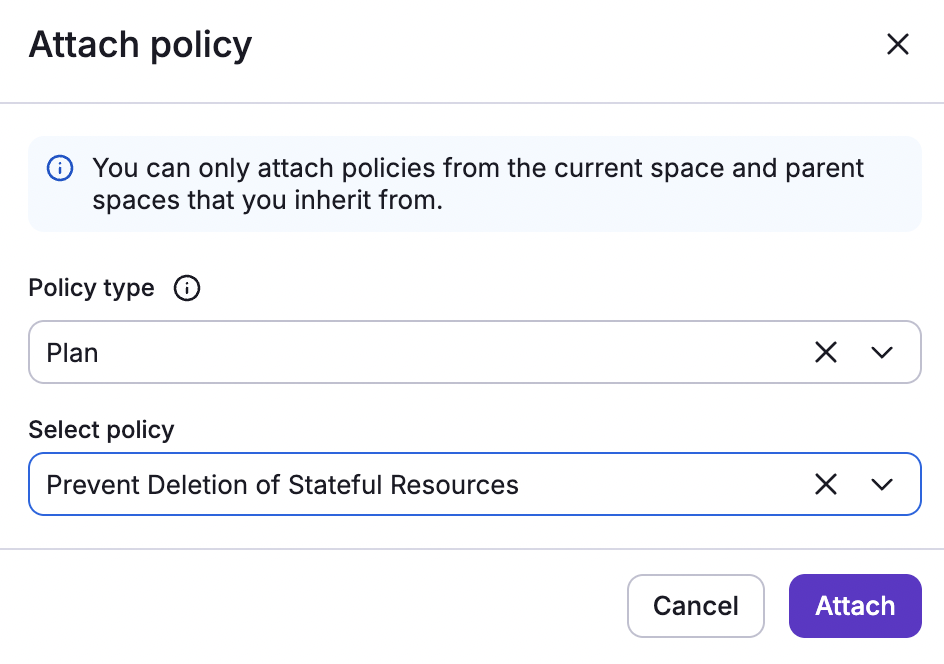

In the web UI, attaching policies is done in the stack management view:

- Navigate to the Ship Infra > Stacks tab.

- Click the name of the stack to attach a policy to.

- Click the Policies tab, then click Attach policy.

- Select policy details:

- Policy type: Select the type of policy from the dropdown list.

- Select policy: Choose the specific policy to add from the dropdown list.

- Click Attach.

Policy workbench»

Sometimes, it takes trial and error to get policies working as intended. This is due to several factors: an unfamiliarity with the concept, a learning curve with the policy language, and/or the slow feedback cycle. Generally, feedback can easily take hours as you iterate through writing a plan policy, making a code change, triggering a run, verifying policy behavior, and rinsing and repeating.

Enter policy workbench. Policy workbench captures policy evaluation events so that you can adjust the policy independently, shortening the entire cycle. In order to use the workbench, you will first need to sample policy inputs.

Sample policy inputs»

Each of Spacelift's policies supports an additional boolean rule called sample. Returning true from this rule means that the input to the policy evaluation is captured, along with the policy body at the time and the exact result of the policy evaluation. You can, for example, capture every evaluation with a simple:

1 | |

1 | |

If that feels a bit simplistic, you can adjust this rule to capture only certain types of inputs. For example, in this case we only want to capture evaluations that returned in an empty list for deny reasons (e.g. with a plan or task policy):

1 | |

1 | |

You can also sample a certain percentage of policy evaluations. Given that we don't generally allow nondeterministic evaluations, you'd need to depend on a source of randomness internal to the input. In this example, we will use the timestamp turned into milliseconds from nanoseconds to get a better spread. We'll also sample every 10th evaluation:

1 2 3 4 | |

1 2 3 4 | |

Why sample?»

Capturing all evaluations sounds tempting, but it will also be extremely messy. Spacelift only shows the 100 most recent evaluations from the past 7 days. If you capture everything, the most valuable samples can be drowned by irrelevant or uninteresting ones. Also, sampling adds a smaller performance penalty to your operations.

Policy workbench in practice»

To show you how to work with the policy workbench, we are going to use a task policy that allowlists just two tasks: an innocent ls, and tainting a particular resource. It also only samples successful evaluations, where the list of deny reasons is empty.

Info

This example comes from our test Terraform repo, which gives you hands-on experience with most Spacelift functionalities within 10-15 minutes.

- On the Enforce Guardrails > Policies tab, click the name of the policy to edit in the workbench.

- Click Show simulation panel on the right-hand side of the screen.

- If your policy has been evaluated and sampled, you will see the policy body on the left-hand side of the screen and a dropdown with timestamped evaluations (inputs) on the right-hand side. The evaluations are color-coded based on their outcomes.

- Select one of the inputs in the dropdown, then click Simulate.

- While running simulations, you can modify both the input and the policy body. If you change the policy body, or select an input that was evaluated using a different policy version, a warning will appear:

- Click Show changes in the warning to view the exact differences between the policy body in the editor and the one used for the selected input.

- When you are satisfied with your updated policy, click Save changes so future evaluations use the new policy body.

Filtering samples»

The samples view offers powerful filtering options to help you quickly locate relevant samples. You can filter samples by:

- Stack name

- Outcome

- Pull request ID

- Push branch

- Stack repository

Once you have identified the sample you want, click the three dots beside its outcome and select Use to simulate to run a simulation with that sample.

Is policy sampling safe?»

Policy sampling is perfectly safe. Session data may contain some personal information like username, name, and IP, but that data is only persisted for 7 days. Most importantly, in plan policies, the inputs hash all the string attributes of resources, ensuring that no sensitive data leaks through this means.

Last but not least, the policy workbench (including access to previous inputs) is only available to Spacelift account administrators.

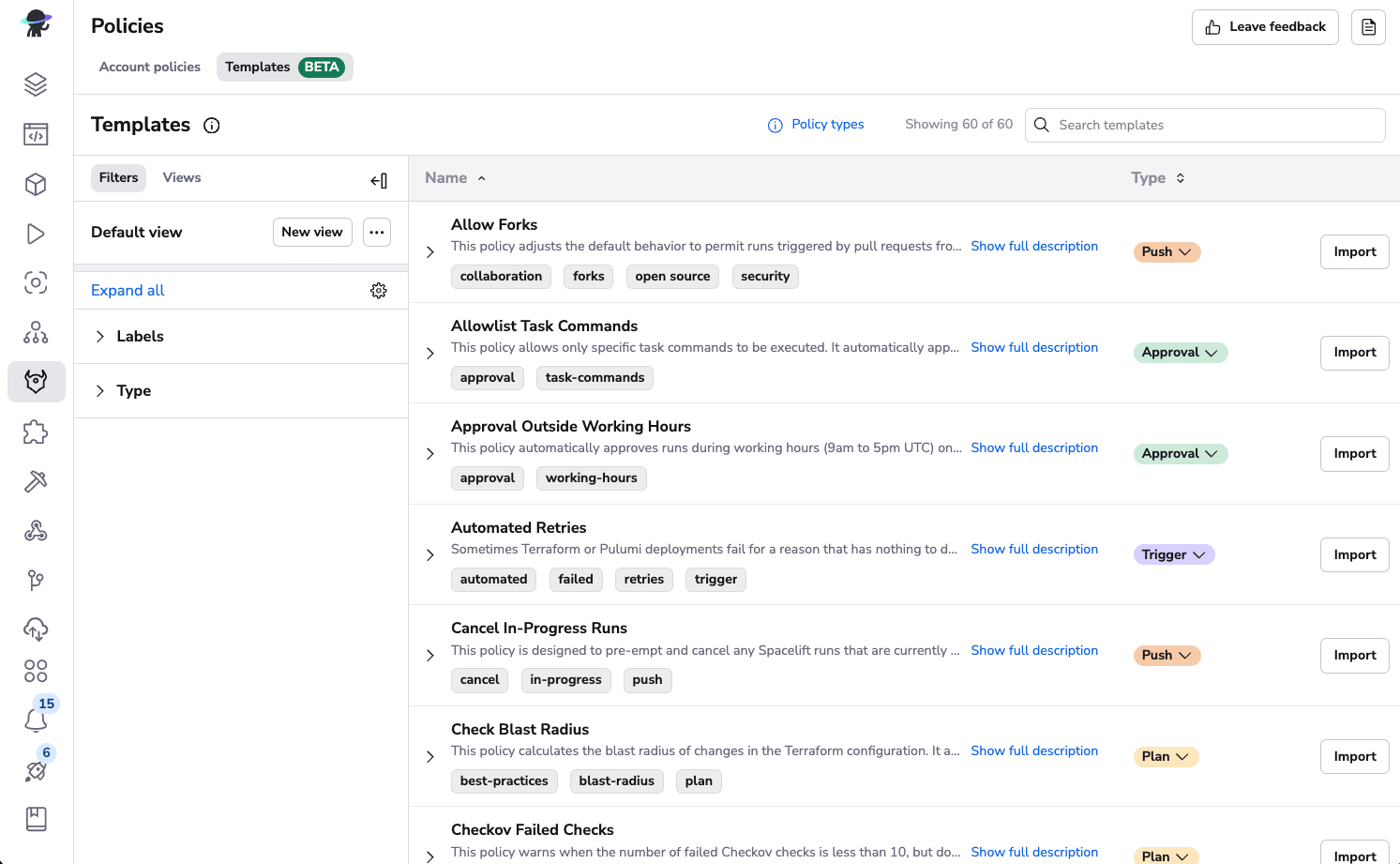

Policy library»

OPA can be difficult to learn, especially if you are just starting out with it. The policy workbench is great for helping you get policies right, but with the policy library, we take it up a notch.

The policy library gives you the ability to import templates as regular policies, directly inside your Spacelift account, that can be easily modified to meet your needs.

On the Enforce Guardrails > Policies tab in Spacelift, you will see a new section: Templates.

You can filter the policies based on the policy type or labels. There are examples available for all supported policy types.

Import policy templates»

- When you find a policy template you would like to add to your account, click Import.

- Edit policy details (optional):

- Name: Enter a descriptive name for the policy.

- Type: Ensure the policy type is correct.

- Space: Select the space to create the policy in.

- Description (optional): Enter a (markdown-supported) description for the policy.

- Labels (optional): Add labels to help sort and filter your policies. You can use

autoattach:labelto attach the policy to stacks or modules with the chosenlabelautomatically.

- Click Continue to edit the policy.

- You'll see an example policy body based on the type you chose. Remove the comments from any rules you'd like to apply and add or change rules as needed.

- Click Create policy. You can always edit policies as needed.

Testing policies»

Info

We invite you to play around with policy examples and inputs in the Rego playground. However, this is not a replacement for proper unit testing.

The whole point of policy-as-code is being able to handle it as code, which involves testing. Testing policies is crucial to make sure they aren't allowing unauthorized actions or too restrictive.

Spacelift uses a well-documented and well-supported open-source language, Rego, which has built-in support for testing. Testing Rego is extensively covered in their documentation so in this section we'll only look at things specific to Spacelift.

Let's define a simple login policy that denies access to non-members, and write a test for it:

| deny-non-members.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 | |

| deny-non-members.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 | |

You'll see that we simply mock out the input received by the policy:

| deny-non-members_test.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

| deny-non-members_test.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

We can then test it in the console using opa test command (note the glob, which captures both the source and its associated test):

1 2 | |

Testing policies that provide feedback to the users is only slightly more complex. Instead of checking for boolean values, you'll be testing for set equality. Let's define a simple run initialization policy that denies commits to a particular branch:

| deny-sandbox.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

| deny-sandbox.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

In the test, we will check that the set return by the deny rule either has the expected element for the matching input, or is empty for non-matching one:

| deny-sandbox_test.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

| deny-sandbox_test.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

Again, we can test the policy in the console using opa test (note the glob, which captures both the source and its associated test):

1 2 | |

Tip

We suggest you always unit test your policies and apply the same continuous integration principles as with your application code. You can set up a CI project using your vendor of choice for the same repository that's linked to the Spacelift project that's defining those policies, to get an external validation.

Policy flags»

By default, each policy is completely self-contained and does not depend on the result of previous policies. However, there are some situations where you want to introduce a chain of policies passing data to one another.

Different types of policies have access to different types of data required to make a decision, and you can use policy flags to pass that data between them.

Say you have a push policy with access to the list of files affected by a push or a PR event. You want to introduce a form of ownership control, where changes to different files need approval from different users. For example, a change in the network directory may require approval from the network team, while a change in the database directory needs an approval from the DBAs.

Approvals are handled by an approval policy but it doesn't retain access to the list of affected files you need. This is where policy flags come in: set arbitrary review flags on the run in the push policy. This can be a separate push policy as in this example, or part of one of your pre-existing push policies. For simplicity, our example will only focus on network.

| flag_for_review.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

| flag_for_review.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

Now, we can introduce a network approval policy using this flag.

| network-review.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

| network-review.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

There are a few things worth knowing about flags:

- They are arbitrary strings and Spacelift makes no assumptions about their format or content.

- They can be reset by policies that set them (see policy flag reset for details).

- They are passed between policy types. If you have multiple policies of the same type, they will not be able to see each other's flags.

- They can be set by any policies that explicitly touch a run: push, approval, plan and trigger.

- They are always accessible through

run'sflagsproperty whenever therunresource is present in the input document.

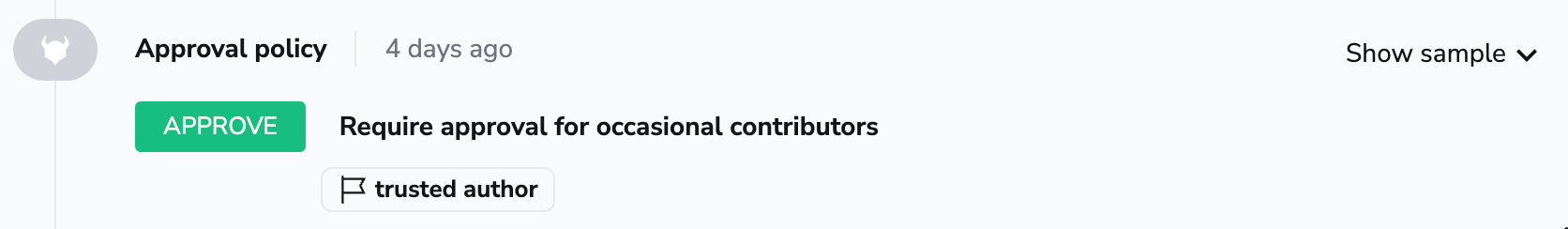

Flags are shown in the Spacelift GUI, so even if you're not using them to explicitly pass the data between different types of policies, they can still be useful for debugging purposes. Here's an example of an approval policy exposing decision-making details:

Backwards-compatibility»

Policies, like the rest of Spacelift functionality, are generally kept fully backwards-compatible. Input fields of policies aren't removed and existing policy "invocation sites" are kept in place.

Occasionally policies might be deprecated, and once unused, disabled, but this is a process in which we work very closely with any affected users to make sure they have ample time to migrate and aren't negatively affected.

However, we do reserve the right to add new fields to policy inputs and introduce additional invocation sites. For example, we could introduce a new input event type to the push policy, and existing push policies will start getting those events. Thus, users are expected to write their policies in a way that new input types are handled gracefully, by checking for the event type in their rules.

For example, in a push policy, you might write a rule as follows:

| backwards-compatibility.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 | |

| backwards-compatibility.rego | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 | |

As you can see, the first line in the track rule makes sure that we only respond to events that contain the pull_requestj field.

Evaluation timeouts»

All policies have a maximum evaluation time to ensure that they do not negatively impact Spacelift's performance. Some policies have a longer timeout due to the complexity of their inputs and expected processing time.

The following table outlines the timeout durations for each policy type:

| Type | Timeout |

|---|---|

| Plan | 45s |

| Notification | 10s |

| Push | 10s |

| All other policies | 5s |

Info

Usually there are multiple policies being evaluated for an event. The combined evaluation time for all policies is 5 minutes